-

View article

#Economy

#EconomySouth Korea: a year after the political crisis, markets are buying the promise of stability

2025/12/17

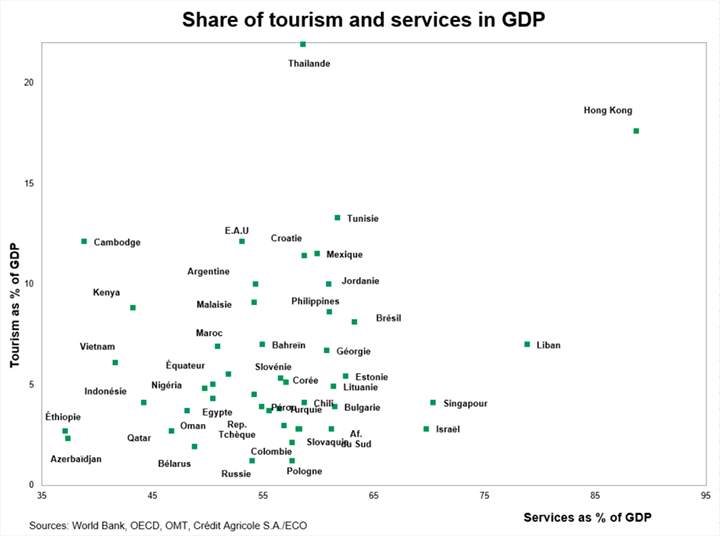

Services and tourism in emerging countries: one of the keys to the crisis

The COVID-19 crisis has many macroeconomic particularities, but one of the most obvious is the violence and duration of the shock to local services in general and tourism in particular. The climate transition also raises questions over the resilience of the tourism business model. Lastly, geopolitics and the renewed necessity of economic sovereignty are emphatically raising the question of how some industrial sectors might be reindustrialised and repatriated. COVID-19, ecology, geopolitics… everything is conspiring to turn up the heat on those countries most vulnerable to these two linked factors: services and tourism.

Yesterday: the service revolution

Economic thinking has never come to a consensus as to whether or not services play a positive role in development. On the one hand, there is the “industrialist” view harking back to the time of Adam Smith, which distinguishes productive labour from unproductive labour, emphasises the damaging effects of deindustrialisation and sees services as an evil which, however necessary, slows total factor productivity and potential growth. On the other hand, there are the upholders of service-led modernisation, whose ranks have obviously swelled as digitalisation has fuelled rapid growth in some economies.

Theoretical debates aside, the reality is inescapable, as is the “service revolution”, which has swept through developed and emerging countries alike, with the services sector now accounting for over 50% of most countries’ GDP. In fact, the share of services in global GDP has steadily increased (reaching 61.2% in 2019) and this profound shift has brought about changes in the drivers of growth, the composition of employment and the level and structure of prices, not to mention its enormous social and political effects. Hannah Arendt put the beginnings of the current great crisis of political legitimacy in the 1970s, with urbanised citizens needing more and more public services and states increasingly unable to meet that need. This ramp-up of services within the economy is thus truly a “permanent revolution”1.

There are many factors behind all this, affecting both output and demand. Besides the obvious technological advances, there is also the rise of the middle class (as income rises, the proportion spent on food decreases while that spent on services increases), low-cost air travel, mass tourism, more women in employment, changes in lifestyles and family structures, and so on. However, the word “service” also refers to two very different realities, with traditional services on the one hand and modern services on the other, representing two worlds that are, economically speaking, diametrically opposed, the former based on high levels of face-to-face interaction (transport, hotels and catering, etc.) and the latter reliant on paperless processes (technology outsourcing, financial services, etc.)

While “modern” services have helped emerging countries get of the ground more quickly, the shift towards a more service-based economy has also fuelled the black economy. Moreover, while the increasing share of services in GDP has been correlated with lower poverty in many countries, service-led development has given rise to new forms of dualism. Development gaps have widened between regions, between “hubs” and the rest, between coastal and central areas and between cities and rural areas, and these disparities lie behind many of our current economic and political difficulties. More generally, with or without digitalisation, Wallerstein’s vision, based on the idea that capitalism creates a core and a periphery, with the former exhausting the latter, seems hard to escape.

Meanwhile, the effect of tourism on developing countries has been just as powerful: as an industry, tourism has a very long value chain and generates many spillover effects by creating jobs, especially given the high proportion of SMEs operating in the sector. Before the crisis, tourism accounted for 10.3% of global GDP, 330 million jobs and 4.3% of total investment.

Tomorrow: the health transition?

Yes, but… all of that was before COVID. Today, those countries that are highly reliant on services, SMEs and tourism are bearing the brunt of the shock, and uncertainty around public health and vaccines risks prolonging the crisis for the sector. Furthermore, those countries that are quickest to emerge from the crisis will increase their market share of international customers (though there has been very little change in comparative advantages in this area2: the Eiffel Tower won’t be going anywhere…).

The International Finance Corporation (IFC) has drawn up a list of discriminating factors that could play a key role over the coming year3. These include obvious factors like location (with all islands adversely affected by the crisis in air travel), but also – and above all – the quality of hotel and road infrastructure. Hotels are going to have to offer not only adequate health services but also high levels of digitalisation, especially now that remote working has created a fast-growing new category of tourists: digital nomads. Countries will have to get their communication strategies just right – like Croatia, for example, which pulled off a masterstroke by continuing to welcome American tourists last July as the rest of Europe pulled up the drawbridge. The country particularly benefited from publicity generated by a report on Dubrovnik, broadcast to 12 million Americans on Good Morning America.

The ability to adapt hotel infrastructure will benefit the wealthiest countries and companies. Luxury hotel chains have already adapted to quarantine procedures. In many countries, hotels are offering luxury stays with the guarantee of vaccinated hotel staff. The Maldives are offering holidays with “No news, no shoes, no masks”… But the system’s effectiveness will also rely on new partnerships between the tourism, healthcare and insurance sectors. Hotels in Phuket are planning private vaccinations this autumn, the United Arab Emirates is partnering with air transport associations to improve “digital health services”, and there is the obvious example of vaccine passports. This is also something major air travel hubs are going to have to get right: their “health transition” will play a crucial role in winning back international business.

What if the Chinese stayed at home?

Countries’ ability to attract regional tourist business will be critical to their recovery trajectory. The IFC has highlighted the fairly clear advantage enjoyed by Asia as a result of its very strong sub-regional infrastructure (e.g. connections between Singapore and the entire region). Fair enough, but what if things don’t return to normal and far fewer Chinese tourists travel outside China than in the pre-COVID world? This could happen not only for health reasons (vaccination rates and official recognition of vaccines) but also for economic reasons: the Chinese government will be doing everything in its power to keep this valuable business within its own borders. Not to mention politics… Tourism was viewed as a driver of domestic development as far back as 1978; for the past few years, however, it has also been seen as a key way of strengthening national sentiment. Ming-era books of letters have been updated and “areas of nationally important scenic and historic interest” (mingsheng4) established, where shopping centres rub shoulders with Buddhist temples with the explicit goal of combining leisure with history.

However, if there is a shock to Chinese tourism, its impact will vary from country to country: Chinese tourists account for nearly 30% of total tourist spend in Thailand and 10% in the United Arab Emirates but a mere 4% in Egypt. The banks of the Nile mainly attract German tourists (17% of the total) and Europeans more generally, including a lot of Eastern Europeans – Poles, Czechs and even Ukrainians – in more or less equal numbers with the Chinese, despite income and population differences. People from Beijing are clearly not all that interested in the pyramids, especially now that a Parthenon and a Sphinx are being built for them back home in Lanzhou, and Xi Jinping is keeping a close eye on the development of Hainan Island, which he is keen to make the “Chinese Hawaii”.

And the rest?

Fortunately, other types of new relationships might emerge. For example, Morocco is banking on developing closer air travel links with Israel, facilitated by the conclusion of the Abraham Accords. For the time being, out of a million Moroccan Jews living in Israel, only around 50-70,000 would consider taking their holidays in Morocco, mainly for religious reasons, with Morocco being the only country in the region to restore synagogues and Jewish cemeteries.

Ultimately, the sector’s ability to manage the health transition, capture regional tourist flows and/or move towards the luxury end of the market will be key to the trajectory of those countries most dependent on tourism. But the risks of reopening will be just as important – a lesson that Dubai, which has recently had to close a number of tourist camps, has learned the hard way. All in all, when it comes to the delicate matter of reconquering the market, countries’ ability to inspire long-term confidence in their public health capability will be crucial. This new type of reputational risk must not be underestimated over the coming years.

1 “Un demi-siècle de montée des services : la révolution permanente”, Jean Gadrey, Le Mouvement Social 2005/2 (issue 211).

2 For France, see Cécilia Mendy’s analysis in the ECO Tour 2021 annual report.

3 “How the Tourism Sector in Emerging Markets is Recovering from COVID-19”, N. Mekharat, N. Traore – IFC, December 2020.

4 “Chine, une nouvelle puissance culturelle ?”, E. Lincot, Les essais médiatiques, 2019.

Tania Sollogoub, Group Economic Studies