European economies in a waiting and transition phase

The past quarter has contributed to heighten uncertainty over the growth trajectories of the major economies, which are facing a global shock to confidence and a reorganisation of their relative competitiveness. The American exceptionalism of growth that has long been above potential, even under the influence of a restrictive monetary policy, has been called into question by the new trade policy, which is acting as a negative shock, leading to a slowdown in growth. Although the European economy will be negatively affected, the asymmetrical nature of the shock makes it less vulnerable. In addition, the desire for greater strategic autonomy on the part of the European economies is taking shape in concrete measures to increase spending on infrastructure and defence, which, by offsetting the negative impact of the trade shock, are putting the Eurozone on an upward growth trajectory, defying the inexorability of a decline in potential growth. All the more reason to put forward the hypothesis of an “European exceptionalism”.

A supply shock for the United States, a demand shock for Europe

In our previous scenarios we highlighted the divergence in growth between the US economy and the economies of Western Europe. The US had exceeded its potential pre-pandemic pace, while GDP in the Eurozone, after a strong post-pandemic recovery, had landed on a modest pace, reopening a negative output gap.

The Trump administration's trade policy draws a sharp contrast with the past narrative of exceptional US growth and Europe lagging behind, particularly affected by the negative shock of higher energy prices. Trump's policies are acting as a supply shock to the US economy, with higher input prices leading to a risk of slower growth and higher inflation. With inflation now five years above target and an increased risk of inflation expectations going off track, the Fed is acting with great caution.

On the other hand, Trump's policies constitute a demand shock for Europe, and in particular for the Eurozone, causing a fall in growth and inflation. However, this shock is asymmetrical in both nature and magnitude, and despite the negative impact on the competitiveness of European companies on the US market, it is having less of an effect on the European economy than on the US economy. The negative impact on European inflation gives the ECB more room to manoeuvre when it comes to cutting interest rates. The decoupling of the two monetary policy stances is therefore set to continue, despite the existing risk of higher inflation linked to retaliatory measures and fiscal stimulus in the Eurozone. In the United Kingdom, the central bank (BoE) is facing higher inflation, which prompts caution, but domestic inflationnary pressures should diminish and we nevertheless expect three rate cuts between the second half of 2025 and Q1 2026.

Growth potential revised upwards and a sustained cycle at the end of the decade

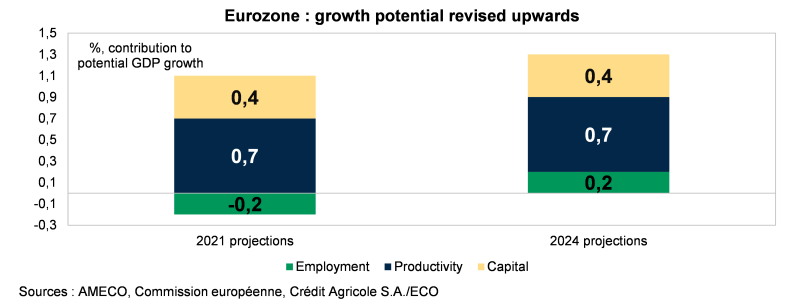

In spite of multiple external shocks, an upward revision of the Eurozone's growth potential on the basis of domestic factors is setting the scene for our scenario for 2025 and 2026. Potential growth is revised upwards for the 2020s compared with the official projections from the start of the decade. Potential growth is projected to accelerate on average over the 2020s compared with the previous decade, breaking with the downward trend that began in the 2010s.

Despite the worsening demographic dynamic, the rise in the employment rate and the participation rate should enable employment to continue to make a positive contribution to growth. Reforms to the labour market and pensions, as well as structural changes in labour force participation and labour hoarding patterns, explain this greater participation in the labour market. This seems compatible with a fall in the equilibrium unemployment rate, which would enable the Eurozone economies to sustain low and falling unemployment rates, without triggering sustained wage dynamics and inflationary pressures. Despite the persistent sluggishness of private investment, the contribution of capital to growth would be maintained with stronger growth in public investment fuelled by the European Recovery Plan, the new German spending paradigm and defence spending. The structural reforms undertaken as part of the European Recovery Plan and the increase in the capital stock should have a positive impact on productivity by the end of the decade.

Around this more dynamic trend growth, a cycle developing in the second half of the decade supported by the strong fiscal impulse provided by public spending. The delay in implementing the European Recovery Plan (NGEU) will concentrate a considerable amount of spending over the next two years, with a positive impact on growth that will operate firstly via the fiscal multiplier, secondly via the deepening of the capital stock and thirdly via higher productivity, the result of higher capital productivity and structural reforms, which are fundamental elements of the plan.

Such an acceleration in growth would also ensure that the debt remains on sustainable trajectories despite the rise in spending, in a context where, with the exception of France, budgetary indicators have improved in the Eurozone and the adjustment efforts are likely to be less demanding than in recent years.

Europe's major economies can count on a more sustained momentum in domestic demand, with investment as the driving force

For the major economies of the Eurozone, we anticipate a common acceleration in domestic demand. This breaks with two years of decline in Germany, is sustained in Italy and Spain, and will be more modest in 2025 in France. It will be driven by stronger growth in private consumption in all countries except Spain, where household spending remains nevertheless very dynamic. The recovery in investment is also contributing, at a very sustained pace in Germany, but also in Italy and Spain. The upturn should materialise with some delay in France.

In France, economic activity grew weakly in the first quarter of 2025. It is expected to rise again, but only slightly, in the second quarter, before accelerating slightly in the second half of the year. The real rebound will come in 2026, driven by the resumption of investment and the initial impact of German government measures. The risks remain mainly on the downside for short-term activity.

In Italy, the incomplete recovery and the recent fall in purchasing power, despite the strength of employment, are limiting the potential for a recovery in household consumption. The positive surprises on investment are likely to continue with the improvement in financing conditions and subsidies for the energy and digital transition. While the recent weakness in industrial orders may weigh on productive investment, construction is showing resilience. Doubts remain, however, about growth potential, with post-pandemic sector allocation favouring less productive sectors.

The German economy is back on the growth track. Although more exposed than its partners to protectionist policies, the economy is likely to be stimulated by the federal investment plan. While the effects will be minimal in 2025 due to planning delays, a significant flow of funds is expected in 2026, with positive knock-on effects for European neighbours and the Eurozone as a whole.

In Spain, easing monetary policy, energy disinflation, rising real incomes and a targeted fiscal stimulus are underpinning domestic demand. The recomposition of the trade balance, marked by a weakening of trade in goods and the continued robustness of market services, particularly tourism, will mean a smaller contribution to growth than in the past. As a result, growth is set to decelerate, a normalisation compared with the years of strong post-pandemic recovery.

In the UK too, GDP growth should be increasingly driven by domestic demand, although the fundamentals of household consumption have deteriorated against the backdrop of the worsened situation on the labour market and restrictive fiscal policy. Household consumption and public spending should be the only components to make a positive contribution.

To learn more, consult our publication “Europe – 2025-2026 Scenario: European economies in a waiting and transition phase”, June 2025